Think of the last time you felt stressed. Perhaps it was something as simple as running late for work, or something more serious, like being in a car accident. When you’re stressed, your heart races, your breathing increases, you feel tense and you are probably not thinking very clearly. Now think of the last time you felt stressed for weeks – or months – at a time. In this case, all of the above were likely true, but you probably also felt exhausted, were moodier than usual and may have even started to have some health issues.

Our dogs experience stress as well. For example, for many dogs, going to the vet is stressful. For others, encountering a stranger or another dog can be stressful. Ongoing sources of stress could include living in poor conditions, being bullied by another animal in the house or being left alone every day for dogs with separation anxiety.

Stress doesn’t only occur in response to negative life events, though. Think about weddings or going to conferences. Most of us agree that getting married is a good thing, and those of use that are nerds for learning, love going to conferences too. But that doesn’t mean it’s not stressful. All of these things are sources of stress – even the enjoyable ones! Let’s take a closer look at what stress is and how it functions.

Definition and function of stress.

Stress is a reaction to change. More specifically, stress is the body’s response to a trigger which disrupts – or potentially disrupts – the status quo. The trigger is known as a stressor. The stressor can be something physical, such as getting sick, that directly challenges the animal’s physiological systems. It can also be a psychosocial stressor which relates to the social environment and social interactions. One example of a psychosocial stressor is a new dog entering the home. In the first case, the dog is actually sick, which always throws the body’s normal systems out of whack. In the second case, the dog social environment has been altered which still disrupts the status quo.

Stressors can also be actual or perceived. Say Shadow is afraid of strangers and barks when they come to visit. The stranger is not actually threatening Shadow’s physical safety. However, if Shadow associates the stranger with threat or believes the stranger might attack him (though, of course, we can’t know what’s actually going on inside Shadow’s head), then that still causes stress.

Here are several more examples of stressors from the human perspective: caring for a loved one with a terminal illness, taking an exam, breaking a bone, the holidays. What about from the dog’s perspective? Going to a dog show, fireworks, breaking a bone, the holidays.

In all of these examples there is some actual or perceived trigger that is threatening (or perceived to threaten) the animal’s status quo. Note that the stress response describes a very specific physiological reaction involving the release of chemicals that help regulate the body’s physiological system.

Stress itself is not “bad”. In fact, in many cases stress – and the stress response – is beneficial and adaptive. Stress helps the body adjust to and cope with change. That is, in fact, the adaptive function of stress. It keeps us alive by preparing our body to cope with a threat or a potential threat. However, stress can be broken down into different categories. This is where things get a little more nuanced. Let’s take a look at the different types of stress.

Acute vs. Chronic Stress

Stress can be acute or chronic. Acute stress occurs when the stressor is relatively short-lived – generally less than a week, though there is no hard and fast time frame. Acute stress could be momentary, for example, slamming on your brakes because the car in front of you stopped quickly, or your dog hearing a sudden, loud noise and startling. Examples of slightly longer acute stressors include rushing to meet a deadline at work or kenneling a dog for several days. Animals usually cope fairly well with acute stress. The physiological response does it’s job – protecting the animal from a potential threat – and then the body carries on as usual. However, in some cases, a single event is severe enough—for example a serious car accident or a physical assault—that it can have lasting effects. Acute stress can also exacerbate symptoms of chronic stress.

Chronic stress occurs when an animal experiences repeated stressors in relatively close succession. In general, stress is considered chronic if it lasts for weeks or longer, with each day involving an extended period of stress (American Psychological Association, 2018; Dhabar and McEwan, 1997; Protopopova, 2016). In contrast to acute stress, chronic stress has a number of serious negative impacts on both mental and physical health.

The Good, The Bad and the…Tolerable

Stress can also be subdivided based on whether it’s harmful, beneficial or neutral. The late Bruce McEwen was one of the leading researchers on the topic of stress. He divides stress into three categories: good stress, tolerable stress and toxic stress (McEwen, 2017).

Good stress. With “good stress,” an individual experiences a healthy challenge that can be a rewarding experience. It involves “rising to a challenge, taking a risk and feeling rewarded by an often positive outcome.” (McEwan, 2017, pg. 2). Good stress is also referred to as eustress. You can think of eustress as a form of stress that increases the animal’s ability to interact effectively with their environment. This could be something like teaching a dog a new skill. Imagine a dog that is learning agility. Foxy starts off unsure of the tunnel, but the trainer does an excellent job of breaking the skill into manageable pieces, letting Foxy go at her own pace and reinforcing her progress. Eventually, the tunnel becomes Foxy’s favorite obstacle! In this case, the situation was initially challenging, but Foxy ended up better off in the long run. However, it was never actually distressing.

Compared to “bad stress”, eustress has gotten very little attention. Just to give you an idea, if you do a search for “distress” in google scholar, you get over 3 million results. Eustress has fewer than 19,000! This follows a general trend in psychology where the tendency is to focus on the mental “illness” aspects of psychology, rather than wellness. Luckily (in my opinion), this has been changing in recent years. But, I digress. The most important point is that stress is not automatically “bad” – it can have positive effects as well.

Tolerable stress. When an individual experiences “tolerable stress” he or she has a negative experience, but is able to cope with that experience, often with help from social support. Both good stress and tolerable stress can result in an experience of growth where the individual is resilient enough to cope with and adapt to the stressful experience. In many cases, the individual emerges from the positive experience stronger than before. Some distress falls into the category of tolerable stress—the experience itself is unpleasant and uncomfortable—but it does not have major long-term effects.

An example of tolerable stress could be taking a shy dog (Teddy) for a walk. For the first couple of walks, Teddy is very anxious, but eventually he gets more comfortable and comes to love walks. This experience then generalizes to walks in other places and Teddy becomes more confident overall. In this case, the experience was initially distressing, but it ended up being beneficial in the long run. (Note that it doesn’t always happen like this! In some cases, the dog may become more and more fearful.)

Toxic stress. Toxic stress is a different beast entirely. When an individual experiences toxic stress, bad things happen and the individual is unable to effectively cope. This could be because they have limited access to coping behaviors. For example, an animal that is kept in a cage and socially isolated does not have access to natural behaviors that may help alleviate the negative impacts of stress. Another reason an animal may not be able to cope is because the animal’s brain cannot adapt to stress for one reason or another. This is often due to stress experienced during development.

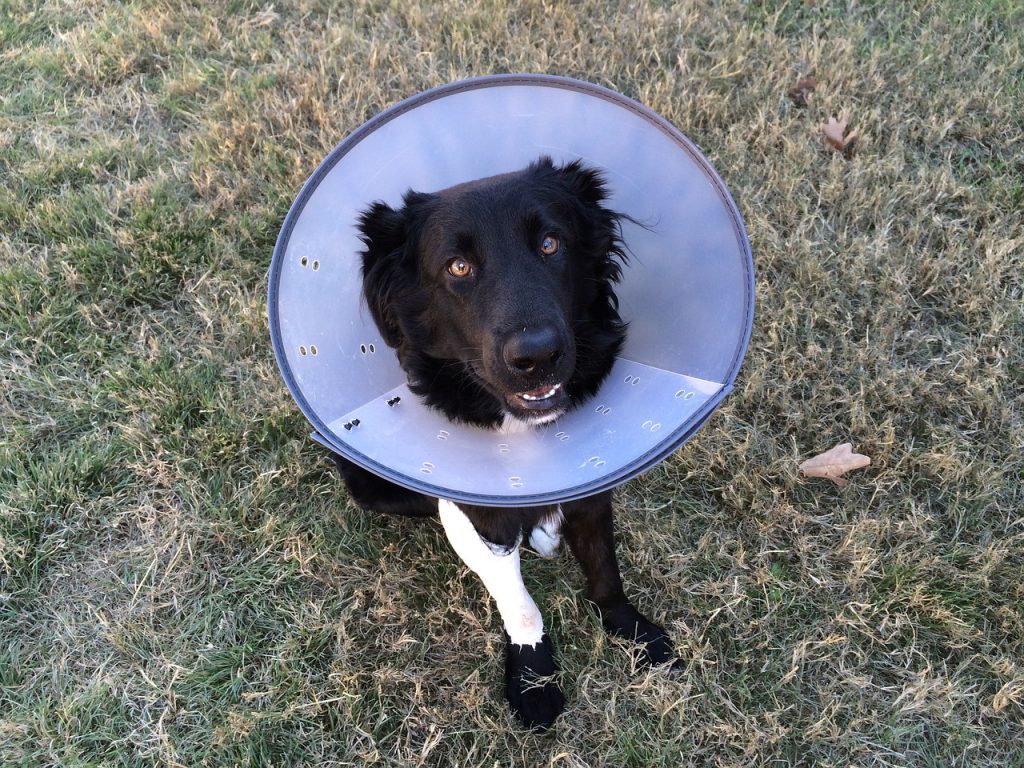

In the case of toxic stress, the animal also experiences distress, but of much greater intensity. The degree of stress exceeds the animal’s ability to cope. This might be a dog that goes through a move and develops separation anxiety or a dog that completely panics over a nail trim. There is a long list of effects from toxic stress. They include anxiety, gastrointestinal issues, impacts on memory and cognition, social impairment and even a shortened lifespan!

In summary, stress occurs when an animal experiences a challenge to its status quo. Stress itself is not good or bad – it is the animal’s ability to cope with that stress that matters. Acute stress is usually less damaging than chronic stress, though intense experiences of acute stress (trauma) can have lasting impacts.

Our job is to monitor animals for signs of distress so that we can either prevent it or intervene as quickly as possible. The ability to cope with a particular stressor will vary for each animal, so it’s important to focus on each individual. Observe their behavior. Signs of stress include muscle tension, freezing, excessive panting, lip licking, flattened ears, yawning, pacing, difficulty settling, struggling, growling, snapping, biting, and attempting to flee. If you suspect an animal is experiencing toxic stress, the first thing to do is remove them from that particular context if possible. Then a long-term management and behavior modification plan can be developed to help them cope moving forward.

If you’d like more information, please join our mailing list to be notified of upcoming courses (see form below), including a multi-week course on stress that will be announced soon. I will also be giving a Research Bites webinar on stress on March 3rd that focuses on how owner stress impacts their dog’s stress. Click here for more information or to register for the webinar.

What questions do you have about stress and its impact on behavior?